Red and white. Why civil war syndrome has not disappeared in a century. White vs Red

The reasons and the beginning of the civil war in Russia. White and red movement. Red and white terror. The reasons for the defeat of the white movement. Civil War Results

The first historians of the Civil War were its participants. Civil war inevitably divides people into “friends” and “strangers”. A kind of barricade lay both in understanding and in explaining the causes, nature and course of the civil war. Day by day we are increasingly realizing that only an objective view of the civil war from both sides will make it possible to approach historical truth. But at a time when the civil war was not history, but reality, they looked at it differently.

Recently (80–90s) the following problems of the history of the civil war are at the center of scientific discussions: the causes of the civil war; classes and political parties in the civil war; white and red terror; the ideology and social essence of “war communism”. We will try to highlight some of these issues.

The inevitable companion of almost every revolution is armed conflict. Researchers have two approaches to this problem. Some see a civil war as a process of armed struggle between citizens of one country, between different parts of society, while others see in a civil war only a period in the country's history, when armed conflicts determine its whole life.

As for modern armed conflicts, their emergence is closely intertwined with social, political, economic, national and religious reasons. Conflicts in their pure form, where only one of them would exist, are rare. Conflicts prevail, where there are many such reasons, but one dominates.

The reasons and the beginning of the civil war in Russia

The dominant feature of the armed struggle in Russia in 1917-1922. there was a "socio-political confrontation. But the civil war of 1917-1922 cannot be understood, given the class side alone. It was a tightly woven ball of social, political, national, religious, personal interests and contradictions.

What started the civil war in Russia? According to Pitirim Sorokin, usually the fall of the regime is not the result of the efforts of revolutionaries, but rather of decrepitude, powerlessness and inability to constructively work the regime itself. To prevent a revolution, the government must go to certain reforms that would remove social tensions. Neither the government of imperial Russia nor the Provisional Government found the strength to carry out the transformations. And since the increase in events required action, they were expressed in attempts at armed violence against the people in February 1917. Civil wars do not begin in an environment of social rest. The law of all revolutions is such that after the overthrow of the ruling classes, their desire and attempts to restore their position are inevitable, while the classes that have come to power try by all means to preserve it. There is a connection between revolution and civil war; in our country, the latter after October 1917 was almost inevitable. The causes of the civil war are the extreme aggravation of class hatred, the debilitating first world war. The deep roots of the civil war must also be seen in the character of the October Revolution, which proclaimed the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Stimulated the outbreak of civil war the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly. The all-Russian power was usurped, and in a society already divided by the revolution, the ideas of the Constituent Assembly and the parliament could no longer find understanding.

It should also be recognized that the Brest peace has offended patriotic feelings the general population, especially officers and intellectuals. It was after the conclusion of peace in Brest that the White Guard volunteer armies began to form actively.

The political and economic crisis in Russia was accompanied by a crisis in national relations. White and red governments were forced to fight for the return of the lost territories: Ukraine, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia in 1918-1919; Poland, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia and Central Asia in 1920-1922 The civil war in Russia went through several phases. If we consider the civil war in Russia as a process, it will become

it is clear that the first act was the events in Petrograd at the end of February 1917. Armed clashes in the streets of the capital in April and July, the Kornilov uprising in August, the peasant uprising in September, the October events in Petrograd, Moscow and several others were in the same series. places

After the emperor’s abdication, the country was swept by the euphoria of “red-bow” unity. Despite all this, February marked the beginning of an immeasurably deeper upheaval, as well as an escalation of violence. In Petrograd and other areas, the persecution of officers began. Admirals Nepenin, Butakov, Viren, General Stronsky and other officers were killed in the Baltic Fleet. Already in the early days of the February Revolution, the bitterness that arose in human souls spilled onto the streets. So, February marked the beginning of the civil war in Russia,

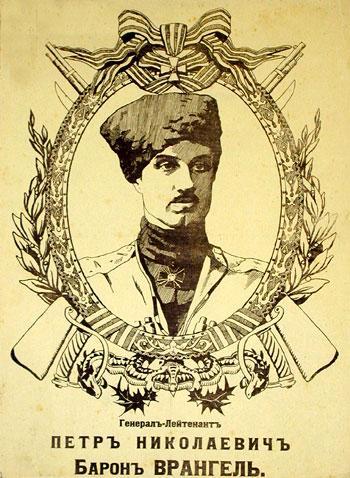

By the beginning of 1918, this stage had largely exhausted itself. It was this position that the Socialist Revolutionary leader V. Chernov ascertained when, speaking at the Constituent Assembly on January 5, 1918, he expressed hope for an early end to the civil war. It seemed to many that the turbulent period was being replaced by a more peaceful one. However, contrary to these expectations, new centers of struggle continued to emerge, and from the middle of 1918 the next period of the civil war began, which ended only in November 1920 with the defeat of the army of P.N. Wrangel. However, the civil war continued after that. Its episodes were the Kronstadt uprising of sailors and Antonovism in 1921, military operations in the Far East, which ended in 1922, Basmachism in Central Asia, mostly eliminated by 1926.

White and red movement. Red and White Terror

At present, we have come to understand that civil war is a fratricidal war. However, the question of what forces opposed each other in this struggle is still controversial.

The question of the class structure and the main class forces of Russia during the civil war is quite complex and needs serious study. The fact is that in Russia, classes and social strata, their relationships are intertwined in a complex way. Nevertheless, in our opinion, there were three major forces in the country that differed in relation to the new government.

The Soviet power was actively supported by a part of the industrial proletariat, the urban and rural poor, some of the officers and the intelligentsia. In 1917, the Bolshevik Party emerged as a freely organized radical revolutionary party of intellectuals oriented toward workers. By mid-1918, it had turned into a minority party, ready to ensure its survival through mass terror. By this time, the Bolshevik party was no longer a political party in the sense in which it was before, since it no longer expressed the interests of any social group, it recruited its members from many social groups. Former soldiers, peasants or officials, having become communists, represented a new social group with their rights. The Communist Party has become a military-industrial and administrative apparatus.

The influence of the Civil War on the Bolshevik party was twofold. Firstly, there was a militarization of Bolshevism, which was reflected primarily in the way of thinking. Communists have learned to think in terms of military campaigns. The idea of \u200b\u200bbuilding socialism turned into a struggle - on the front of industry, the front of collectivization, etc. The second important consequence of the civil war was the Communist Party's fear of the peasants. Communists have always been aware that they are a minority party in a hostile peasant environment.

Intellectual dogmatism, militarization, combined with hostility towards the peasants created in the Leninist party all the necessary prerequisites for Stalin's totalitarianism.

The forces opposing the Soviet regime included the large industrial and financial bourgeoisie, landowners, a large part of the officers, members of the former police and gendarmerie, and a part of highly qualified intelligentsia. However, the white movement began only as a rush of convinced and courageous officers who fought against the communists, often without any hope of victory. White officers called themselves volunteers, driven by the ideas of patriotism. But at the height of the civil war, the white movement became much more intolerant, chauvinistic, than at the beginning.

The main weakness of the white movement was that he failed to become a unifying national force. It remained almost exclusively a movement of officers. The white movement could not establish effective cooperation with the liberal and socialist intelligentsia. Whites were suspicious of workers and peasants. They did not have a state apparatus, administration, police, or banks. Embodying themselves as a state, they tried to make up for their practical weakness by brutally imposing their own orders.

If the white movement could not rally the anti-Bolshevik forces, then the Cadet Party failed to lead the white movement. The cadets were a batch of professors, lawyers, and entrepreneurs. In their ranks there were enough people capable of establishing a functioning administration in the territory liberated from the Bolsheviks. Nevertheless, the role of the Cadets in national policy during the civil war was insignificant. There was a huge cultural gap between the workers and peasants, on the one hand, and the Cadets, on the other, and the Russian revolution was presented to most of the Cadets as chaos, rebellion. Only the white movement, according to the Cadets, could restore Russia.

Finally, the largest population group in Russia is the fluctuating part, and often just the passive one, which observed the events. She was looking for opportunities to do without the class struggle, but was continuously drawn into it by the active actions of the first two forces. These are the urban and rural petty bourgeoisie, the peasantry, the proletarian strata who wanted a "civil peace", part of the officers and a significant number of representatives of the intelligentsia.

But the division of forces offered to readers should be considered conditional. In fact, they were closely intertwined, mixed together and scattered throughout the vast territory of the country. This situation was observed in any region, in any province, regardless of in whose hands the power was. The decisive force, which largely determined the outcome of revolutionary events, was the peasantry.

Analyzing the beginning of the war, only with great conventionality can we talk about the Bolshevik government of Russia. Allotted in 1918, it controlled only part of the country. However, it declared its readiness to rule the whole country after it dissolved the Constituent Assembly. In 1918, the main opponents of the Bolsheviks were not white or green, but socialists. The Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries opposed the Bolsheviks under the banner of the Constituent Assembly.

Immediately after the dispersal of the Constituent Assembly, the Socialist-Revolutionary Party began preparations for the overthrow of the Soviet regime. However, soon the Socialist-Revolutionary leaders became convinced that there were very few people willing to fight weapons under the banner of the Constituent Assembly.

A very sensitive blow to attempts to unite the anti-Bolshevik forces was dealt to the right by supporters of the military dictatorship of the generals. The main role among them was played by the Cadets, who strongly opposed the use of the requirement to convene the Constituent Assembly of the 1917 model as the main slogan of the anti-Bolshevik movement. The Cadets headed for a one-man military dictatorship, which the Socialist-Revolutionaries christened right-wing Bolshevism.

The moderate socialists, who rejected the military dictatorship, nevertheless made a compromise with supporters of the general dictatorship. In order not to push the Cadets away, the all-democratic bloc “Union of the Revival of Russia” adopted a plan to create a collective dictatorship - the Directory. To manage the country, the Directory had to create a business ministry. The Directory was obliged to lay down its powers of the all-Russian power only before the Constituent Assembly after the end of the struggle with the Bolsheviks. At the same time, the “Revival Union of Russia” set the following tasks: 1) the continuation of the war with the Germans; 2) the creation of a single solid power; 3) the revival of the army; 4) restoration of disparate parts of Russia.

The summer defeat of the Bolsheviks as a result of the armed uprising of the Czechoslovak corps created favorable conditions. So the anti-Bolshevik front arose in the Volga and Siberia, immediately formed two anti-Bolshevik governments - Samara and Omsk. Having received power from the hands of Czechoslovakians, five members of the Constituent Assembly - V.K. Volsky, I.M. Brushvit, I.P. Nesterov, P.D. Klimushkin and B.K. Fortunatov - formed the Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly (Komuch) - the highest state body. Komuch handed executive power to the Board of Governors. The birth of Komuch contrary to the plan of creating the Directory led to a split in the Socialist Revolutionary elite. Its right-wing leaders, led by N.D. Avksentiev, ignoring Samara, went to Omsk to prepare from there the formation of an all-Russian coalition government.

Declaring himself temporary supreme authority until the convening of the Constituent Assembly, Komuch called on other governments to recognize him as the state center. However, other regional governments refused to recognize Komuch as the rights of a national center, regarding it as a party Socialist-Revolutionary power.

The Socialist-Revolutionary politicians did not have a concrete program of democratic transformations. The issues of the grain monopoly, nationalization and municipalization, the principles of the organization of the army were not resolved. In the field of agrarian policy, Komuch limited himself to a statement on the immutability of ten points of the land law adopted by the Constituent Assembly.

The main goal of foreign policy was the continuation of the war in the Entente. Betting on Western military assistance was one of Komuch’s largest strategic miscalculations. The Bolsheviks used foreign intervention in order to portray the struggle of the Soviet government as patriotic, and the actions of the Socialist Revolutionaries as anti-national. Broadcast statements by Comuch about the continuation of the war with Germany to a victorious end came into conflict with the mood of the masses. Komuch, who did not understand the psychology of the masses, could rely only on the bayonets of his allies.

The anti-Bolshevik camp was especially weakened by the confrontation between the Samara and Omsk governments. Unlike the one-party Komuch, the Provisional Siberian government was a coalition. At the head of it stood P.V. Vologda. The left wing in the government was composed of the Social Revolutionaries B.M. Shatilov, G.B. Patushinskii, V.M. Krutovsky. The right side of the government is I.A. Mikhailov, I.N. Serebrennikov, N.N. Petrov ~ occupied cadet and promo-narchist positions.

The government program was formed under considerable pressure from its right wing. Already in early July 1918, the government announced the abolition of all decrees issued by the Council of People's Commissars, and the liquidation of the Soviets, the return to the owners of their estates with all the inventory. The Siberian government pursued a policy of repression against dissidents, the press, assemblies, etc. Komuch protested against such a policy.

Despite sharp controversy, the two rival governments had to negotiate. At the Ufa state meeting, a “temporary all-Russian power” was created. The meeting concluded its work by electing a Directory. The structure of the latter was elected N.D. Avksentiev, N.I. Astrov, V.G. Boldyrev, P.V. Vologodsky, N.V. Tchaikovsky.

In its political program, the Directory declared the struggle to overthrow the power of the Bolsheviks, annul the Brest Peace and continue the war with Germany as its main tasks. The short-term nature of the new government was emphasized by the clause that the Constituent Assembly was to meet in the near future - January 1 or February 1, 1919, after which the Directory would resign.

The directory, having abolished the Siberian government, could now seem to implement a program alternative to the Bolshevik one. However, the balance between democracy and dictatorship was upset. Samara Komuch, who represented democracy, was dissolved. The Socialist-Revolutionary attempt to restore the Constituent Assembly failed. On the night of November 17-18, 1918, the leaders of the Directory were arrested. The directory was replaced by dictatorship A.V. Kolchak. In 1918, the civil war was a war of ephemeral governments, whose claims for power remained only on paper. In August 1918, when the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Czechs took Kazan, the Bolsheviks could not recruit more than 20 thousand people to the Red Army. The popular Socialist-Revolutionary Army numbered only 30 thousand. During this period, the peasants, dividing the land, ignored the political struggle waged by parties and governments. However, the establishment by the Bolsheviks of comedians caused the first outbreaks of resistance. From that moment on, there was a direct correlation between the Bolshevik attempts to dominate the village and peasant resistance. The more zealously the Bolsheviks tried to impose “communist relations” in the countryside, the more severe the resistance of the peasants.

White, having in 1918. several regiments were not contenders for state power. Nevertheless, the white army A.I. Denikin, originally numbering 10 thousand people, was able to occupy a territory with a population of 50 million people. This was facilitated by the development of peasant uprisings in areas held by the Bolsheviks. N. Makhno did not want to help the whites, but his actions against the Bolsheviks contributed to the breakthrough of the whites. Don Cossacks rebelled against the communists and cleared the path of the advancing army of A. Denikin.

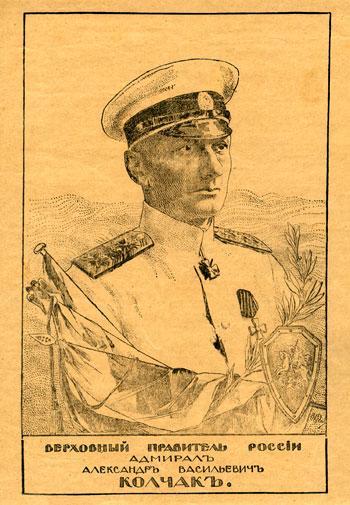

It seemed that with the promotion of the role of dictator A.V. Kolchak appeared in white leader, who will lead the entire anti-Bolshevik movement. In the provision on the temporary arrangement of state power, approved on the day of the coup, the Council of Ministers, the supreme state power was temporarily transferred to the Supreme Ruler, all the Armed Forces of the Russian state were subordinate to him. A.V. Kolchak was soon recognized as the Supreme Ruler by the leaders of other white fronts, and the Western Allies recognized him de facto.

The political and ideological ideas of the leaders and ordinary participants in the white movement were as diverse as the movement itself was socially heterogeneous. Of course, some part sought to restore the monarchy, the old, pre-revolutionary regime in general. But the leaders of the white movement refused to raise the monarchist banner and put forward a monarchist program. This applies to A.V. Kolchak.

What positive did the Kolchak government promise? Kolchak agreed to convene a new Constituent Assembly after restoring order. He assured Western governments that there could be “no return to the regime that existed in Russia until February 1917,” the broad masses of the population would be endowed with land, and religious and ethnic differences would be eliminated. Confirming the complete independence of Poland and the limited independence of Finland, Kolchak agreed to “prepare decisions” on the fate of the Baltic states, Caucasian and Trans-Caspian peoples. Judging by the statements, the Kolchak government was in a position of democratic construction. But in reality, everything was different.

The most difficult issue for the anti-Bolshevik movement was the agrarian question. Kolchak failed to solve it. The war with the Bolsheviks, while it was being waged by Kolchak, could not guarantee the transfer of landowner land to the peasants. The same profound internal contradiction was noted in the national policy of the Kolchak government. Acting under the slogan of “one and indivisible” Russia, it did not reject as an ideal the “self-determination of peoples”.

Kolchak actually rejected the demands of the delegations of Azerbaijan, Estonia, Georgia, Latvia, the North Caucasus, Belarus and Ukraine put forward at the Versailles Conference. Refusing to create an anti-Bolshevik conference in the regions liberated from the Bolsheviks, Kolchak pursued a policy that was doomed to failure.

The relations of Kolchak with the allies, which had their own interests in the Far East and Siberia and pursued their own policies, were complex and contradictory. This greatly complicated the position of the Kolchak government. A particularly tight knot was tied in relations with Japan. Kolchak did not hide his antipathy towards Japan. The Japanese command responded with active support for the atamanism, which flourished in Siberia. Small ambitious people like Semenov and Kalmykov, with the support of the Japanese, managed to create a constant threat to the Omsk government in the deep rear of Kolchak, which weakened it. Semenov actually cut off Kolchak from the Far East and blocked the supply of weapons, ammunition, provisions.

Strategic miscalculations in the field of domestic and foreign policy of the Kolchak government were exacerbated by errors in the military field. The military command (generals V.N. Lebedev, K.N. Sakharov, P.P. Ivanov-Rinov) led the Siberian army to defeat. Betrayed by all, and allies and allies,

Kolchak resigned as Supreme Ruler and transferred it to General A.I. Denikin. Not justifying the hopes placed on him, A.V. Kolchak died courageously, like a Russian patriot. The most powerful wave of the anti-Bolshevik movement was raised in the south of the country by Generals M.V. Alekseev, L.G. Kornilov, A.I. Denikin. Unlike the little-known Kolchak, they all had big names. The conditions in which they had to act were desperately difficult. The volunteer army, which Alekseev began to form in November 1917 in Rostov, did not have its own territory. In terms of food supply and troop recruitment, it was dependent on the Don and Kuban governments. The volunteer army had only the Stavropol province and the coast with Novorossiysk; only by the summer of 1919 did it conquer for several months a vast area of \u200b\u200bthe southern provinces.

The weak point of the anti-Bolshevik movement in general and in the south was especially the personal ambitions and contradictions of the leaders M.V. Alekseev and L.G. Kornilova. After their death, all power passed to Denikin. The unity of all forces in the fight against the Bolsheviks, the unity of the country and the authorities, the widest autonomy of the outskirts, fidelity to agreements with allies in the war - these are the main principles of the Denikin platform. The entire ideological and political program of Denikin was based on the mere idea of \u200b\u200bpreserving a single and indivisible Russia. The leaders of the white movement rejected any significant concessions to the supporters of national independence. All this was in contrast with the promises of the Bolsheviks of unlimited national self-determination. The reckless recognition of the right to secession gave Lenin the opportunity to curb destructive nationalism and raised its prestige much higher than the leaders of the white movement.

The government of General Denikin was divided into two groups - the right and the liberal. Right - a group of generals with A.M. Drago-world and A.S. Lukomsky at the head. The liberal group consisted of cadets. A.I. Denikin took the position of the center. The most distinctly reactionary line in the politics of the Denikin regime manifested itself on the agrarian question. On the territory controlled by Denikin, it was supposed: to create and strengthen small and medium-sized peasant farms, to destroy latifundia, to leave the landowners small estates on which a cultural economy could be maintained. But instead of immediately proceeding with the transfer of landowner land to the peasants, an endless discussion of the draft land law began in the commission on the agrarian question. As a result, a compromise law was passed. The transfer of part of the land to the peasants was to begin only after the Civil War and end after 7 years. In the meantime, an order was put into effect on the third sheaf, according to which a third of the grain collected went to the landowner. Denikin's land policy was one of the main reasons for his defeat. Of the two evils — the Leninist surplus-appraisal or the Denikin requisition — the peasants preferred the lesser.

A.I. Denikin understood that without the help of his allies, defeat awaited him. Therefore, he himself prepared the text of the political declaration of the commander of the armed forces of southern Russia, sent on April 10, 1919 to the commanders of the English, American and French missions. It spoke of the convening of a national assembly on the basis of universal suffrage, the establishment of regional autonomy and broad local self-government, and land reform. However, things did not go beyond broadcast promises. All attention was paid to the front, where the fate of the regime was decided.

In the fall of 1919, a difficult situation developed for the Denikin army at the front. This was largely due to a change in the mood of the broad peasant masses. Peasants who rebelled in a territory subject to white paved the way in red. The peasants were a third force and acted against those and others in their own interests.

In the territories occupied by both the Bolsheviks and the whites, peasants fought a war with the authorities. The peasants did not want to fight either for the Bolsheviks, or for the whites, or for anyone else. Many of them fled into the woods. During this period, the green movement was defensive. Since 1920, there has been less and less threat emanating from the whites, and the Bolsheviks are more decisively imposing their power in the countryside. The peasant war against state power swept all over Ukraine, the Black Earth region, the Cossack regions of the Don and Kuban, the Volga and Urals basin and large regions of Siberia. In fact, all the bread-producing regions of Russia and Ukraine were a huge Vendée (in the figurative sense - counter-revolution. - Note Ed.).

From the point of view of the number of people participating in the peasant war and its influence on the country, this war overshadowed the war of the Bolsheviks and the whites and exceeded it in its duration. The green movement was the decisive third force of the civil war,

but it did not become an independent center, claiming power more than on a regional scale.

Why didn’t the movement of the majority of the people prevail? The reason is the way of thinking of the Russian peasants. Greens defended their villages from outsiders. The peasants could not win, because they never sought to seize the state. The European concepts of a democratic republic, the rule of law, equality and parliamentarism, which the Socialist-Revolutionaries introduced into the peasant milieu, were beyond the comprehension of the peasants.

The mass of peasants participating in the war was heterogeneous. From the peasant milieu, both insurgents, keen on the idea of \u200b\u200b“robbing the looted”, and leaders, eager to become new “kings and gentlemen,” advanced. Those who acted on behalf of the Bolsheviks, and those who fought under the command of A.S. Antonova, N.I. Makhno, adhered to similar norms in behavior. Those who robbed and raped as part of the Bolshevik expeditions were not much different from the rebels Antonov and Makhno. The essence of the peasant war was liberation from all power.

The peasant movement put forward its own leaders, people from the people (suffice it to name Makhno, Antonov, Kolesnikov, Sapozhkov and Vakhulin). These leaders were guided by the concepts of peasant justice and obscure echoes of the platform of political parties. However, any party of peasants was associated with statehood, programs and governments, while these concepts were alien to local peasant leaders. The parties pursued a nationwide policy, and the peasants did not rise to the realization of national interests.

One of the reasons that the peasant movement did not triumph in spite of its scale was the political life characteristic of each province, which went against the rest of the country. While in one province the greens were already defeated, in another the uprising was just beginning. None of the green leaders took action outside the immediate vicinity. This spontaneity, scale and breadth included not only the power of movement, but also helplessness in the face of a systematic onslaught. The Bolsheviks, who had great power, had a huge army, had militarily overwhelming superiority over the peasant movement.

Russian peasants lacked political consciousness - they did not care what the form of government in Russia was. They did not understand the significance of parliament, freedom of the press and assembly. The fact that the Bolshevik dictatorship withstood the test of civil war can be seen not as an expression of popular support, but as a manifestation of an unformed national consciousness and political backwardness of the majority. The tragedy of Russian society was the lack of interconnectedness between its various layers.

One of the main features of the civil war was that all the armies participating in it, red and white, Cossacks and greens, went the same path of degradation from serving a cause based on ideals to looting and atrocities.

What are the causes of red and white terror? IN AND. Lenin stated that the Red Terror during the years of the civil war in Russia was forced and became a response to the actions of the White Guards and interventionists. According to the Russian emigration (S.P. Melgunov), for example, the Red Terror had an official theoretical justification, had a systemic, governmental character, the White Terror was characterized "as excesses due to unbridled power and revenge." For this reason, the red terror in its scale and cruelty was superior to white. Then a third point of view arose, according to which any terror is inhuman and should be abandoned as a method of struggle for power. The comparison “one terror is worse (better) than another” is incorrect. No terror has a right to exist. The appeal of General L.G. Kornilov to the officers (January 1918) “do not take prisoners in battles with the Reds” and the recognition of the Chekist M.I. Latsisa that in the Red Army resorted to similar orders against whites.

The desire to understand the origins of the tragedy gave rise to several research explanations. R. Conquest, for example, wrote that in 1918-1820. the terror was carried out by fanatics, idealists - "people who can find some features of a peculiar perverse nobility." Among them, according to the researcher, can be attributed to Lenin.

Terror during the war was carried out not so much by fanatics as by people deprived of all nobility. We will name only some instructions written by V.I. Lenin. In a note to the Deputy Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic E.M. Sklyansky (August 1920) V.I. Lenin, evaluating the plan born in the bowels of this department, instructed: “A wonderful plan! Finish it with Dzerzhinsky. Under the guise of “greens” (we will later knock them down), we will go 10–20 versts and outweigh the kulaks, priests, and landowners. Bonus: 100,000 rubles for the hanged man. ""

In a secret letter to members of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the RCP (B.) Dated March 19, 1922, V.I. Lenin proposed taking advantage of the famine in the Volga region and seizing church property. This action, in his opinion, “should be carried out with merciless decisiveness, certainly not stopping at anything and at the very the shortest time. The greater the number of representatives of the reactionary clergy and the reactionary bourgeoisie we manage to shoot on this occasion, the better. It is now necessary to teach this audience a lesson so that for several decades they don’t dare to think about any resistance ”2. Stalin perceived the Leninist recognition of state terror as a high-government deed, a power based on force, and not on the law.

It is difficult to name the first acts of red and white terror. Usually they are associated with the outbreak of civil war in the country. Everyone executed the terror: officers - participants in the ice campaign of General Kornilov; KGB officers who received the right to extrajudicial reprisal; revolutionary courts and tribunals.

It is characteristic that the right of the Cheka to extrajudicial killings, composed by L.D. Trotsky, signed by V.I. Lenin; granted unlimited rights to the tribunals by the people's commissar of justice; People's Commissars of Justice, Internal Affairs and the Head of the Council of People’s Commissars (D. Kursky, G. Petrovsky, V. Bonch-Bruevich) endorsed the Red Terror Decree. The leadership of the Soviet Republic officially recognized the creation of a non-rule-of-law state, where arbitrariness became the norm of life, and terror the most important tool for maintaining power. Lawlessness was beneficial to the warring parties, as it allowed any action with reference to the enemy.

The commanders of all armies, apparently, never submitted to any control. This is a general wildness of society. The validity of the civil war shows that the differences between good and evil have faded. Human life has depreciated. The refusal to see an adversary as a person prompted violence on an unprecedented scale. Settling accounts with real and imaginary enemies has become the essence of politics. Civil war meant the extreme bitterness of society and especially of its new ruling class.

"Litvin A. Red and White Terror in Russia 1917-1922 // Historical History. 1993. No. 6. P. 47-48.1 2 Ibid. P. 47-48.

Murder M.S. Uritsky and the attempt on Lenin on August 30, 1918 provoked an unusually violent response. In retaliation for the murder of Uritsky, up to 900 innocent hostages were shot in Petrograd.

A significantly larger number of victims is associated with the attempt on Lenin. In the early days of September 1918, 6185 people were executed, 14,829 were imprisoned, 6407 in concentration camps, and 4068 people became hostages. Thus, the assassination attempts against the Bolshevik leaders contributed to the revelry of mass terror in the country.

Simultaneously with the red, white terror was rampant in the country. And if the Red Terror is considered to be the implementation of state policy, then probably the fact that the Whites in 1918-1919 should be taken into account. also occupied vast territories and declared themselves as sovereign governments and state entities. The forms and methods of terror were different. But they were used by supporters of the Constituent Assembly (Komuch in Samara, the Provisional Regional Government in the Urals), and especially by the white movement.

The coming to power of the Constituentists in the Volga region in the summer of 1918 was characterized by reprisals against many Soviet workers. One of the first departments created by Comuch was state security, military courts, trains, and death barges. On September 3, 1918, they brutally suppressed the workers ’performance in Kazan.

The political regimes established in 1918 in Russia are quite comparable primarily in terms of predominantly violent methods of resolving issues of organizing power. In November 1918 A.V. Kolchak, who came to power in Siberia, began with the expulsion and murder of the Social Revolutionaries. It is hardly possible to speak of the support of his policy in Siberia in the Urals, if out of about 400 thousand red partisans of that time 150 thousand acted against him. The government of A.I. Denikin. In the territory captured by the general, the police were called state guards. By September 1919, its number reached almost 78 thousand people. Osvag's reports informed Denikin about robberies and looting, it was during his command that 226 Jewish pogroms occurred, as a result of which several thousand people died. White terror turned out to be just as pointless to achieve its goal as any other. Soviet historians calculated that in 1917-1922. 15-16 million Russians were killed, of which 1.3 million were victims of terror, banditry, and pogroms. The civil, fratricidal war with millions of human victims turned into a national tragedy. Red and white terror became the most barbaric method of struggle for power. Its results for the country's progress are truly disastrous.

The reasons for the defeat of the white movement. Civil War Results

We single out the most important causes of the defeat of white movement. The bet on Western military assistance was one of the miscalculations of the whites. The Bolsheviks used foreign intervention to present the struggle of the Soviet government as patriotic. The policy of the allies was self-serving: they needed anti-German Russia.

A deep contradiction is noted in the national policy of the whites. Thus, Yudenich’s non-recognition of Finland and Estonia as an independent in fact already was probably the main reason for the failure of the whites on the Western Front. Non-recognition of Poland by Denikin made her a constant opponent of the whites. All this contrasted with the promises of the Bolsheviks of unlimited national self-determination.

In a relationship military trainingWhite had all the advantages of combat experience and technical knowledge. But time worked against them. The situation was changing: in order to replenish the melting ranks, White also had to resort to mobilization.

The white movement did not have broad social support. The White Army was not equipped with everything necessary, so it was forced to take carts, horses, and supplies from the population. Local residents were drafted into the army. All this restored the population against whites. During the war, mass repression and terror were closely intertwined with the dreams of millions of people who believed in new revolutionary ideals, and tens of millions lived nearby, preoccupied with purely everyday problems. The fluctuations of the peasantry played a decisive role in the dynamics of the civil war, as well as various national movements. During the civil war, some ethnic groups regained their previously lost statehood (Poland, Lithuania), and Finland, Estonia and Latvia acquired it for the first time.

For Russia, the consequences of the civil war were catastrophic: a huge social shake-up, the disappearance of entire estates; huge demographic losses; breaking economic ties and tremendous economic devastation;

the conditions and experience of the civil war had a decisive influence on the political culture of Bolshevism: the winding up of internal party democracy, the perception by the broad party masses of the installation of methods of coercion and violence in achieving political goals - the Bolsheviks seek support in the lumpenized sections of the population. All this paved the way for strengthening repressive elements in public policy. The Civil War is the greatest tragedy in the history of Russia.

I already quoted a couple of years ago from the book Through the Hell of the Russian Revolution by Nikolai Reden. Former midshipman, whose share went to so many of the most amazing events and adventures that lasts for three lives. Nikolai Reden visited the basement of the Cheka, in the winter of 1918 he was able to escape from St. Petersburg to Finland. From there he moved to Estonia. He fought in the White Army, General Yudenich, first as a spotter of an armored train, then in the crew of one of six tanks. He can be said to be one of the "pioneers" of the Russian tank troops. Unfortunately, in the civil war ...

After the defeat of Yudenich, together with two dozen officers, he was able to escape from Estonia on the last Russian minesweeper in the Baltic under the Andreevsky flag. The minesweeper reached Denmark, where the crew interned. After this, Reden moved to the United States, where he lived the rest of his life.

Memories of Reden is one of the rarest examples in emigrant literature of how the author was able to rise above class and personal insults and see the civil war as it was.

In connection with the discussion that developed, why the “Reds” won the civil war and whether their victory was the result of total cruelty, foreign (Latvian-Chinese-Jewish) intervention, and who fought for this war, I consider it useful to once again bring this historical document ...

OFFICERS

.... As in any other, the White Army did not have two absolutely identical people, but the officers of this army could be conditionally divided into four categories. If at least two officers who belonged to one of the categories met in the regiment, they sought to imitate the entire personnel.

One category of white officers bore more responsibility than others for the loss of prestige by the anti-Bolshevik movement among the masses of the population of Russia. Part of the officer corps consisted of the military, hardened during World War II, the revolution and the Red Terror. They were driven by a desire for immediate revenge. Unfortunately, as a result of five years of chaos and bloodshed, this category of people has increased numerically. They were primarily responsible for losing the prestige of the White Army. They were alien to any remorse. They did not ask and did not give mercy, robbed and terrorized the civilian population, shot deserters and prisoners from the Red Army. In front of their soldiers, such officers stood in the pose of Robin Hoods, who disregarded the law, playing the part of fair, but ruthless atamans. Their attitude towards the authorities changed depending on the circumstances - from impeccable correctness to complete disobedience. When I visited the units of such commanders, I had the impression that I had returned to the Middle Ages and ended up in a gang of robbers.

Where irregular groups dominated, infinite cruelty and atrocities reigned, the White Command could not do anything with them. At the front, there was too little strength to devote reliable, disciplined units to police functions. In addition, despite their atrocities, the illegal groups nevertheless represented, on the whole, very combat-ready units. These considerations compelled White’s command to be “generally indifferent” to complaints of looting.

If the officers who turned into robbers and murderers represented one extreme, then the other were people completely demoralized by the events of previous years. Some of them came to the front from the rear, but not because they obeyed a sense of duty or sought to defend their beliefs in the struggle, but because they were not in demand in other places. Most of them were forcibly mobilized into the Red Army, in the ranks of which they fought after the sleeves. Having been captured by the whites, they perceived the change in their position as a natural course of events. Often the conversion from red to white lasted only a few hours.

I was struck by the passivity of these officers. Their apathy could not be considered false: they simply lost all hope for the future. They came into motion, like worn-out machines, mechanically following commands and completing any task. They did not live, but existed, did not fight, but clung to life. Spiritually and emotionally, they became dead.

The third type of white officer was a stark contrast to the first two. This category consisted of those who did not reckon with reality. They were in relative calm, instilling in themselves the belief that nothing had changed. Many of them managed to save at least something from their former state. Most of them served behind the front line, indulging in a safe game, in which the most important thing was compliance with the norms and rules of army life. Obviously, their ridiculous complacency could continue only as long as the other officers and soldiers remained willing to fight at the front, but this consideration did not stop censuring any person who did not comply with their rules of the game.

As a special group, supporters of strict discipline in the White Army did not present such a danger as desperate bandit elements, or were not as unreliable as passive, meek officers. But indirectly, they contributed significantly to the initiation of antagonism in the ranks of the whites. The very appearance of these purebirds infuriated, especially in connection with the obviousness that they require a lot, and give little for the success of the White Cause.

However, all these groups were, in a sense, take root. They could not find a common platform for action and could not survive long enough in a war if it were not for the fourth category of officers, which was the backbone of the White Movement.

It is not easy to classify the people in the latter category. They represented a wide range of social strata and political beliefs. Among them there were aristocrats whose philosophy of life was the motto: “For faith, the king and the Fatherland”; liberals; representatives of the landlord class, many generations of which served the state; students of universities and other higher educational institutionswhose ideals were trampled by the Bolsheviks. But all these social differences were smoothed out by their two fundamental circumstances: love for the motherland and willingness to make sacrifices for the sake of their principles.

During the bloody Civil War, officers of this category developed an unwritten strict code of conduct, which they strictly adhered to. One of the main requirements is self-discipline, and it is very severe. Perhaps this demand was an involuntary reaction to the anarchy and disorder that accompanied the revolution, but these people suffered severe difficulties without whining and complaining, when they received orders, they tried to do the impossible.

Dejected by senseless destruction, despising their less scrupulous associates, the White Army patriots treated the civilian population almost knighthoodly.

Nothing inspired the soldiers more than the personal courage of this category of officers. Young or old, they did not think about danger. For days on end, these military men courageously carried out their duty and were ready for action in any emergency. I have repeatedly witnessed the highest strength of their spirit.

Fearlessness was not uncommon among these people who carried on their shoulders the main burden of armed struggle in the Civil War.

White officers who performed their duty with such dedication were few in number, but excitement and determination became the most important factor in this war. Without them, the White Movement could not have gained strength. Only such people were able to withstand confusion, weak command of the troops; only they saved the prestige of the White Cause among the civilian population; only they brought organization into the ranks of various rabble in the White Army; only they were an obstacle to the victory of the Reds.

The civil war in Russia was a conflict of irreconcilable principles. One side of the conflict was represented by the Reds, who advocated the unconditional dictatorship of the proletariat, the other - by the White, who considered such a dictatorship to be a usurpation of power and sought to eliminate it. For those who clearly understood this, there was no compromise, but most of the soldiers in both armies did not delve into problems so distant from them.

Both sides resorted to mobilizing peasants on military service and forced to fight for goals alien to ordinary soldiers. Between the warring parties, the Russian peasant relied on fate and dutifully served in the army that called him first. The warranties of white and red seemed equally unacceptable to him, but he had no choice. As a rule, the soldiers of the warring armies did not have enmity towards each other and considered opponents to be the same victims of circumstances as themselves.

When the conscript was captured by the opposing side, he was genuinely indignant if he was treated as a prisoner of war. If he was allowed to serve in the enemy army, he very quickly adapted to new conditions and fought no worse than the rest of the soldiers. Usually absurd circumstances accompanied the capture, and the captives were incredibly naive.

Mass desertion was not uncommon. Because of him, the White Army lost and acquired soldiers

But not all Russian soldiers fought without conviction. Both the White and the Red Army had entire regiments, the personnel of which were uncompromisingly opposed to the enemy, who never betrayed their beliefs. Contrary to the claims of the Bolsheviks about the class nature of the war, representatives of all social, national and economic strata were in the battle ranks of both sides.

For example, most industrial workers were reliable and loyal parts of the Red Army, but there were many notable exceptions. The ranks of the whites included enough railway workers and highly skilled workers. In two regions, factory workers fled to Siberia with the families and property in connection with the advance of the Red Army. The best divisions of Kolchak were subsequently formed from them.

On the other hand, most Cossacks were clearly anti-Bolshevik, but many young people served with the Reds. In the Red Army, entire Cossack regiments were formed from them. Each of the participants in the Civil War determined its own destiny, and what served as a decisive factor in this was difficult to determine.

WAR, TACTICS, CONDITIONS

The conditions in which the Civil War in Russia took place differed from the conditions in which the world war was fought. Long-term combat positions were the exception rather than the rule. Soldiers rarely had to experience the oppressive monotony of trench life. The concentration of artillery, the density of fire, the intense aerial bombardment - all these monstrous technical inventions that made an individual soldier extremely helpless, were not widespread. But unlike the colossal nervous tension experienced by a Russian soldier during the First World War, Civil presented superhuman demands on his physical endurance.

The soldiers who served in the White and Red armies needed to be strong enough to move at a fast pace. Their life was a continuous change of offensives and retreats, attacks and counterattacks, raids deep into enemy territory without respite. Soldiers, well-equipped and physically strong, were fully laid out in these extremely dynamic operations. But the soldier’s stamina was undermined by the severity of revolutionary time: a constant lack of the most necessary excluded the possibility of restoration of forces.

The most acute problem was the lack of food. Officers and soldiers on the fronts were constantly starving.

In the first months of the Civil War, the Quartermaster Service of the Northwest Army had very modest means for procuring food and actually had no sources of supply. The food ration was half a pound of bread per day and half a pound of dried fish once or twice a week. If the soldiers wanted to survive, they had to look for additional means of subsistence.

The theater of war was a territory with a poor peasant population devastated by war and revolution. Instead of living the products of their labor, the peasants themselves depended on the troops controlling their village. It happened that some enterprising soldier found a bag of worm flour or a basket of rotten potatoes. As a rule, cooks had to invent dishes from grass, roots, water and handfuls of flour.

.... Each officer and soldier wore the uniform in which he enlisted in the army, and usually did not expect to get something new. The soldiers of the warring armies mostly wore the uniform of a protective color of the established pattern, but soldiers in civilian clothes often came across. One of my fellow officers carried the brown cage suit and gray cap throughout the war. Only on his shoulders were always shoulder straps with the designation of rank.

While the clothes were repairable, the owner diligently repaired them in the presence of free time. But over time, the form still turned into rags. Many soldiers wore trousers sewn from burlap. Underwear and socks were a great luxury. However, in the meager wardrobe of a soldier, boots were considered the most valuable. When the sole wore out, it was knocked out with paper and secured with twine. There was a grueling struggle to maintain a thin layer of skin that was thinning day by day. The boots were not thrown out until one top was left, however, the percentage of barefoot soldiers and officers was steadily increasing.

The lack of clothing, in addition to the fact that it entailed insecurity from the weather, caused other troubles. The Reds and the Whites practically fought in the same rags, it was difficult to distinguish them from each other. As a result, numerous tragic incidents occurred during each battle: they mistook their soldiers for the enemy and opened fire on them, which caused numerous casualties.

Weapons in the White Army were also bad. While the Northwest Army was fighting the Bolsheviks on Estonian territory, the Whites replenished their weapons from arsenals concentrated in Estonia. But when the war spread to the territory of Russia, it was required to find new sources. All was missing: artillery pieces, ammunition, rifles.

Both sides used standard Russian weapons, the problem was simply the seizure of weapons and ammunition in sufficient quantities. But, starting in June (1918), the long-awaited deliveries from abroad began to arrive. But their expectations never came true.

The infantry received cartridges not suitable for Russian rifles. Hundreds of British rifles arrived without any cartridges. From France, guns were constantly delivered, which were torn after the first shot. Artillery received whole boxes of shells with defects. A significant part of them was not torn. New engines for airplanes did not have the speed needed to take the cars off the ground. Instead of improving the material and technical support of the army, the situation only worsened.

But worse than uncertainty and physical difficulties were psychological factors that contributed to the bitterness in battle. Cruelty is inherent in any war, but incredible ruthlessness reigned in the civil war in Russia. The parties considered each other criminals and did not capture soldiers, with the exception of draftees. White officers and volunteers knew what would happen to them if they were captured by the Reds: I have often seen terribly disfigured bodies with shoulder straps carved on their shoulders. On the other hand, few communists could have avoided the brutal measures of influence of the white counterintelligence. As soon as the party affiliation of the communists was established, they were hung on the first bitch.

RESULTS OF THE WAR

White strongholds collapsed in all regions of Russia, their armies were defeated. But it would be a mistake to explain the victories of the Reds with the initial strength of the Soviet system or the impact of the ideals of communism on the masses. Regarding material and organizational resources, both sides were exhausted to the limit, both sides enjoyed little support from the masses, but the White Movement was characterized by more weaknesses.

From a military point of view, the Red forces turned out to be more significant, occupying the central regions of the country. The councils controlled the most populated areas, as well as administrative and transport hubs. Their human resources were proportionally more numerous, and troop coordination was easier. Although the Reds fought on several fronts, they were under a single command and could be transferred from one sector of the front to another when the need arose.

White forces were divided into four isolated groups: the Siberian Army under the command of Admiral Kolchak with a supply base in distant Vladivostok; South under the command of General Denikin, who controlled the Crimea, as well as the Don and Kuban, inhabited by Cossacks; The Northwest under the command of General Yudenich with hostile Estonia in the rear and the Northern Army under the command of General Miller, deployed in uninhabited areas and entirely dependent on the help of allies. Admiral Kolchak was considered to be the nominally supreme leader of the White Movement and commander in chief of the white forces, but due to circumstances, the commander of each army actually had to rely on his own resources. It did not happen that any two white armies could act together or coordinate their military operations.

The volatile nature of the white and red armies should hardly be considered a less important factor. In the initial stages of the Civil War, the White forces were superior to the Reds in fighting spirit and discipline. But most of their power and enthusiasm was wasted on scattered skirmishes with local communist gangs. By the time the confrontation acquired the scale of war, the ranks of the whites were replenished by conscripts of dubious loyalty.

While the level of white combat readiness declined, in the Red Army, it increased. The most combat-ready part of the Red Army was workers of industrial centers, sailors, political refugees from neighboring countries: Finns, Estonians and Latvians. This contingent joined the ranks of the Reds later and sharply increased the combat effectiveness of the army.

The specifics of the Civil War required special qualities from the officers. Among them, much more skills acquired from traditional military education were valued for such qualities as enterprise and adaptation to circumstances. Not burdened with traditions, the Bolsheviks had great freedom in choosing commanders, based on their professional merits and dedication to the cause of communism. On the other hand, in the White Army, the selection for command posts was less thorough: on the grounds of nobility, friendly relations, family and corporate relations, etc. As a result, the White forces were often inferior in the art of maneuver and combat operations.

If whites had no military advantages, then in the political sphere their situation was even worse. At the head of the Soviets was a group of decisive figures, united by the bonds of a common faith and a concrete vision of the future. The White movement was led by an alliance of professional military and liberals of all stripes, who were united only by the desire to overthrow the Bolsheviks, but who were unable to work out a mutually acceptable, long-term and constructive program. And the reds and whites ruled very poorly, but the reds were more purposeful.

Communication with foreign countries and military support from abroad were the main advantages of the whites, but even so, the isolated position of the Soviets turned out to be good for them in many respects. Red leaders were not burdened with diplomatic considerations, while white leaders, taking help from abroad, put themselves in a dependent position. The Reds did not wait for help and accordingly developed their own plans, which did not need to coordinate with anyone. White, however, relied on factors that they could not control, and as a result, their calculations were often not justified.

In fact, the military assistance provided by the white allies was negligible. In the north of Russia, several battles between the Reds and the Allies took place, the active operations of the Czechoslovak divisions caused the Bolsheviks a lot of trouble, but the military operations of the Allies in Russia were carried out sporadically. In each individual case, the implementation of military plans was complicated by the rivalry between the allies, personal preferences and political excesses in the homeland. At times, the contingent of foreign troops did more than what was required of them, but they always maintained their right to non-participation in hostilities, and the White Command did not know what to expect from day to day.

While the presence of foreign troops did not significantly change the situation on the fronts, it served to the benefit of the propaganda activities of the Soviet authorities. On Bolshevik posters, in appeals and in newspapers, White Army soldiers were branded as foreign mercenaries, and although the population was restrained with such accusations, in the end the propaganda did its job. Playing on hostility to everything foreign, the Reds managed to set up public opinion against whites. There was practically nothing to oppose this powerful psychological pressure. White leaders were guided by old ideas: they believed that wars were fought only on the battlefields, and completely did not take into account the moral condition of the population in the rear of their troops. The whites never tried to conduct large-scale propaganda, no efforts were made to influence the consciousness of the masses or to discredit the Soviet regime in their eyes, systematically using convincing arguments.

Another psychological factor played an even more important role in attracting the sympathy of the population. Peasants treated white and red with the same distrust, but were more afraid of whites. In turbulent revolutionary times, almost every peasant committed an act of violence that oppressed him: in some cases it was a small misconduct, in others it was a more serious crime, such as robbery and even murder. The peasant did not like the Reds, but he believed that under their power he would not be called to account for old crimes. On the other hand, he linked the victory of White with the danger of answering the court for his misconduct. Feeling guilty and fear of punishment forced him to opt for the Reds as the lesser of two evils.

In assessing the forces of the warring parties, one advantage of the Reds outweighed the rest: the caliber of their leaders. Lenin’s mentality, combined with his understanding of the psychology of the masses, Trotsky’s dynamism and fanaticism, Stalin’s purposefulness and administrative talent, had in themselves enough weight to tip the scales towards the victory of the Reds. They were opposed by Kolchak, Denikin and Yudenich - three extremely capable professional military men, but who had neither the training nor the temperament to play the role of state or political leaders.

Kolchak among them was the most striking example of a figure endowed with both advantages and disadvantages, which caused the defeat of whites. Being personally immaculately honest, he did not try to question the goodwill of his assistants or the promises of diplomats and politicians. As a courageous person and patriot, he could not admit that many people tend to skip their duty and be guided by selfish motives. A hereditary military man, Kolchak was accustomed to command and had no idea about managing through compromises, about how to achieve goals by attracting public opinion to his side.

Only two white leaders showed hope of becoming a serious threat to Bolshevism in Russia. General Kornilov, who, unfortunately for his followers, died in battle at the beginning of the Civil War, and general, Baron Wrangel, who demonstrated military talent and political insight, but called to leadership when the White Army ridge was already killed. The question of whether these two figures could turn the course of events in a different direction remains in the realm of speculation.

In reality, the cause of the White movement should be considered losing from the very beginning. The whites sought to solve the problems of Russia either by restoring the previous monarchical system, or by creating a state with a constitutionally democratic form of government. Both decisions were impossible: the first - because of the mood of the population, the second - because of the indifference and low education of people. Only a completely new political movement, such as later emerged in Italy and Germany, could defeat Bolshevism. But if the White movement in Russia accepted fascist-Nazi ideas and won, then it is doubtful that the total amount of its achievements would be more significant than that of the Soviet government, or that the history of Russia would become less tragic from this.

ABOUT RED

Among Russian emigrants, there are many charitable societies that are doing great work to help their compatriots adapt to new living conditions. Non-governmental organizations of another type, such as clubs, are only engaged in maintaining previous ties. Such organizations perform natural humanitarian functions.

However, there are other organizations with more ambitious goals. Russian political organizations continue to exist in Paris, Berlin and other large cities of the West. They are represented by people of all political convictions: monarchists who unite around a candidate for a nonexistent Russian throne and who receive mail awards for supporting his claims; liberals who protest against the methods of violence in Soviet Russia without any hope of success; socialists who also lost their sense of reality and who scold the communists for treason.

Whatever the particularities of their political views, they all strive for a new violent coup in Russia and make absolutely fantastic plans to overthrow the Soviets at a safe distance.

A few contacts with them were enough to delve into the course of this active, but meaningless activity.

I was convinced that the only honest way out for those who thought about their country and wanted to do something was to return immediately to Russia. For a long time I seriously hatched such plans.

Repatriation could take place in one of three ways. The simplest and easiest of them was to return as a repentant prodigal son, who unconditionally accepted the symbol of the communist faith. But although my mind was reconciled with the fact of the power of the Reds, feelings rebelled against this. I could not forget the period of red terror, and although the Communists did a great job of cleaning their party from the cruel, fanatical elements that turned the first years of the Soviet rule into a nightmare, in many ways they remained the same. Cruel, gratuitous hatred still possesses them, they continue to speak pompous, meaningless platitudes and demand from the followers of blind faith in the triumph of their ideas. Anyone who doubts the ultimate success of a communist experiment cannot hope that he will be able to maintain honesty, soul, and even life among the communists.

The second method was to illegally infiltrate Russia and wage an underground struggle with the Communists, an enterprise completely meaningless and inconclusive; and I had no desire to participate in another conspiracy against the regime.

The revolution proved that the Russian people are not ready for a democratic form of government, that in the interests of preventing anarchy, they probably need a firm hand. While the monarchy performed its functions properly, leftist ideas were safely restrained within the framework of ideology, the revolution did not threaten society. But since continuity was violated, the restoration of tsarist power could mean only one of two things: the establishment of a regime similar to the pompous, doomed to death Second Empire in France, or a progressive dictatorship that differs from the Soviet one only in name. Consequently, it was not worth the blood and suffering that a new coup was fraught with. Communists have demonstrated the ability to act in any situation. They completed the destructive period of the revolution and began the implementation of a constructive program of a national scale. Russia's interests demanded that the Bolsheviks be given the opportunity to implement their plans. This was completely clear to me, I did not want to provide the services of any organization that intended to stop Russia's movement along the path of progress.

There was a third way: surrender to the mercy of the Soviet authorities. But because of my past, I couldn’t count on active participation in rebuilding Russia. The Soviet police would constantly keep me under surveillance, and at best I would have to doom myself for a long period of spiritual stagnation.

ABOUT AMERICA AND RUSSIA

Analyzing the situation, I came to a standstill. I understood that I could not remain Russian and at the same time live the rest of my life abroad. On the other hand, I did not see the opportunity to return to Russia in the near future. What bothered me most was that I did not feel the urgent need to return. Suddenly, the truth revealed to me: in my worldview, habits and affections, I became an American.

The process of my Americanization was slow and completely unconscious. The first impressions of the country were chaotic: America seemed a maze of irreconcilable contradictions, a seething human mass deprived of national unity. I came across representatives of all walks of life: farmers, workers, office workers, professors, businessmen, students, ministers, politicians - they all thought differently, did not put social origin at the forefront, and did not refer to their rich experience. Gradually, I became interested in the history of America.

For months, I eagerly devoured volume after volume of J. Bancroft, F. Parkman, G. Adzms, E. Channing, and JB MacMaster. I became interested in the primary sources and read the letters of J. Washington, J. Adam-s, T. Jeffereon and J. Madison.

I realized that America in many ways retained both idealism and the ruthlessness of its founders, although it did not remain the same for even

two successive generations.

Representatives of the new were dissolved in the previous, but in turn introduced new genes, constantly updating society.

I also threw everything acquired into this melting pot and thus strengthened my connection with America.

But, thinking and feeling like an American, I did not lose the feeling of kinship with Russia. Both feelings were easily combined, because America and Russia have amazingly much in common. Enthusiasm is common to both countries, which often looks funny, but at times helps them reach astounding heights; Both are alien to sophistry, justifying injustice; both peoples have a sense of humor.

Perhaps this similarity is due to the size of their territories and wealth of resources. Perhaps this is a consequence of the multinational population that created these countries. Whatever the reasons, I know that the peoples of Russia and America are equally endowed with qualities that allow me to be proud when it happens to mention that I am an American, a former Russian.

P.S.

Reading Reden, I could not get rid of the strange sensation of the mirror similarity of the "red" and "white" in the description of the main moving social groups of the war, and in the descriptions of the state of the army and in supply and in cruelty and in despair and greatness. Two beggars, stripped, hungry, and hated by hate, the armies fought to the death for the right to inherit Russia that they had tormented themselves. And Reden’s conclusions are mercilessly accurate - what happened to Russia after 1917 could not help but blame the Bolsheviks, who only seized the collapsed power, and ALL Russia was to blame, failing to find the strength to meet the challenge of the times. And the fact that in the end Russia went to the Communists, according to Reden, this is not the worst option. There were much worse ...

However, each reader will have their own conclusions.

For me personally, the discussion with the current “monarchists” and “whites” has lost all meaning and interest. There is nothing to argue about. You can love the “White” (I myself, if at that time I were to lie on the side of the “Red”), you can study their history, admire their courage, but today, seriously confessing the ideology of the “White Renaissance” can only finally break with reality Reconstructor. However, like the "red renaissance" ...

Holy White Army

White vision melts, melts ...

The old world is the last dream:

Youth-Valor-Vendée-Don.

Marina Tsvetaeva,

(Russian poetess)

In the Civil War, whites acted, on the one hand, the most powerful counter-revolutionary anti-Bolshevik force, on the other hand, they were the bearers of a superclass, nationwide idea of \u200b\u200bstatehood, combining the traditions of both Romanov’s Russia and February, revolutionary Russia. Therefore, their counter-revolutionary nature was half-hearted. They were ardent opponents of the Bolshevik October, but for the most part they shared the ideas and values \u200b\u200bof the liberal reformist February 1917, especially the idea of \u200b\u200bconvening a Constituent Assembly.

The tough intransigence of the whites with respect to the reds, in contrast to the Socialist Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and other Russian socialists, was explained by reasons of both a national-patriotic and class nature. In the eyes of the whites, the reds (Bolsheviks) were an anti-national, cosmopolitan force that violated all international obligations of Russia, including its allied obligations, distributing the country's territories to the left (conditions of the Brest Peace), seizing power by force and establishing unheard of terror against entire classes and population groups in Russia.

From the point of view of the whites, the reds were like a plague, infecting the social lower classes with blind hatred and a passion for destruction for everything sacred to the Russian patriot: Motherland, Religion, Church, Tradition. That is why with the Bolshevik commissars and all the active participants in the Reds, the Whites did not stand on ceremony. A loop or bullet was always ready for them. This inevitably exacerbated the bitterness of the parties in the fratricidal Civil War.

At the same time, the “white terror" in its scale could not be compared with the "red terror", due to the lack of white political organization like the Bolshevik party, with its uncompromising class ideology justifying the inevitability of terror. According to A.G. Zarubina, V.G. Zarubina, during the entire Civil War, whites executed almost more than 10 thousand people, which is several dozen times less than the red ones.

The officers formed not only the main backbone of the White movement, but also acted as its ideological organizer and inspirer. The social composition of the Russian officers was variegated, but for the most part the officers came from poor, not-so-noble families, and many of them received officer ranks on the fronts of World War II. This determined the democracy of the white officer movement itself. Of course, there were many monarchists among the officers and participants of the White Movement, and even supporters of a return to Romanov’s order. That's just almost all the leaders of the White Movement (Kornilov, Alekseev, Kaledin, Kolchak, Denikin and others) shared the republican and "February" revolutionary beliefs and values. But at the same time, everyone was decisively opposed to that soldier’s anarchy and the democratic “mess” that reigned in the Russian army and in society in 1917.

In fact, the failed Kornilov revolt in August 1917 was the ideological embryo of the future White movement, which advocated the restoration of centralism, the rule of law and the territorial integrity of the country. It is no coincidence that all of its main participants (Kornilov, Denikin, Markov, Romanovsky, Lukomsky and others), imprisoned in Bykhov prison and freed in November 1917, were the main organizers of the White movement that arose in the south of Russia. The south of the country, removed from the Bolshevik Center became the main gathering place for all the implacable opponents of the Bolsheviks, the main forge of the White movement and, finally, the main anti-Bolshevik white front. It is here, in the South, in the Don and Kuban, Generals M.V. Alekseev and L.G. Kornilov at the end of November 1917 began to form the first volunteer military formations of the White Guards.

It is a fact that during this period the whites did not have the strength and means to confront the Bolsheviks, who at that time, certainly enjoyed the support of the majority of the population. Even the Cossacks were deaf to the calls of the former tsarist generals, to throw off the "yoke" of the Bolsheviks and restore the pre-October rule of law and the integrity of the country. The Cossacks were alien to the white slogan "about a united and indivisible Russia." They dreamed of wide autonomy. The Cossacks had plenty of land, and while their Bolsheviks did not get it, they evaded the call to join the White Army.

The “white volunteers” who were in the Don and joined the ranks of the small volunteer army at the end of 1917 were all from cadets and officers. It is no coincidence that General L. G. Kornilov, meeting people who came to the Don who were ready to fight against the Bolsheviks, exclaimed with undisguised irritation: “Are these all officers, but where are the soldiers?” (According to L. S. Semennikova) And the soldiers who came from the peasants and workers supported Soviet power.

The social policy of the Bolsheviks (“factories for the workers”, “land for the peasants”, “peace for all working people”) at the first stage looked very attractive to the vast majority of the country. In practice, this meant that whites were initially doomed to a quick and quick defeat from the “reds" - the Bolsheviks.

However, the strictly repressive social and economic policy of the Bolsheviks caused an unprecedented social split and polarization in society, which significantly expanded the geography and social composition of the participants in the anti-Bolshevik movement. Later, representatives of the intelligentsia, the petty bourgeoisie, the Cossacks (due to the Bolshevik policy of talking to the Don), peasants and even workers (for example, into Kolchak’s army) joined the white army who voluntarily, and more often after mobilization.